In Shibata City, Niigata Prefecture, right next to the famous Tsukioka Onsen—known as the “Hot Spring for Beautiful Skin”—lies a place of quiet yet overwhelming presence: the Token Denshokan Akitsugu Amata Memorial Museum.

To many, “Japanese swords” might seem intimidatingly high-brow or something purely from the world of anime and games. However, a visit here reveals that these blades are not mere weapons; they are the ultimate fusion of Japanese aesthetics and craftsmanship. In this report, we delve into the life of Akitsugu Amata, a master swordsmith who reached the pinnacle of modern sword-making and was designated a Living National Treasure.

1. Who Was Akitsugu Amata, the “Modern-Day Masamune”?

First, we must understand the man behind the museum. Active from the Showa to the Heisei eras, Akitsugu Amata was designated a Preserver of Important Intangible Cultural Properties—commonly known as a “Living National Treasure”—in 1997.

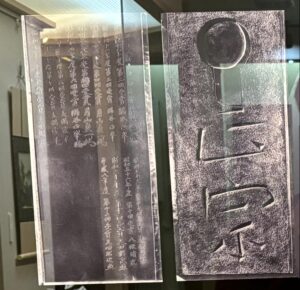

Crucial to understanding his greatness is his history with the Masamune Prize, often called the “Nobel Prize of the sword world.” This prize is not awarded simply for being “skilled.” it is only given when a work possesses a level of spirituality and technique that rivals the legendary blades of the past. If no work meets this standard, the prize is “Not Awarded”—a strictness evidenced by a 14-year drought where no winner emerged.

Master Amata won this prestigious Masamune Prize a record-breaking three times. This feat speaks volumes about his unparalleled status in the world of modern swordsmithing.

Photos of Amata displayed in the museum show a sharp glint in his eyes, yet he radiates a gentle compassion. Until his final years, he lived by the mantra: “Speak with flames, listen to iron.” Facing the inorganic material of iron, he engaged in a spiritual dialogue through fire, water, and his own soul. This seeker-like devotion is what gives his blades their profound nobility.

2. The Challenge of “Koto”: Obsession with Self-Made Steel

Amata’s lifelong pursuit was to balance the beauty and strength found in the legendary blades of the Kamakura period, known as “Koto” (Old Swords). Even with modern science, perfectly replicating these ancient masterpieces is considered nearly impossible.

While most modern swordsmiths use Tamahagane steel supplied by the Association for the Preservation of Japanese Art Swords, Amata was different. To truly recreate the texture of ancient blades, he insisted on “Jika-Seigo”—smelting his own steel from scratch.

The museum details his exhaustive process of selecting iron sand, mixing soils, and chasing the ideal steel. To create his own steel, he had to sift through earth and gather materials countless times. To an ordinary person, this level of dedication might seem like madness. Yet, it is only by overcoming such hardships that one can reach a realm others cannot.

Descriptions of his Masamune Prize-winning works reveal the staggering beauty of his Jigane (the surface steel). Its mysterious expression resembles a clear water surface or a deep, silent forest—a masterpiece born from his self-taught, refined smelting techniques.

3. The Moment Iron Gains a Soul: The Sword-Making Process

A major highlight of the museum is the exhibition showing the step-by-step process of creating a Japanese sword, complete with actual samples. The journey from a block of iron to a finished blade involves over ten rigorous stages:

- ① Tanren (Forging): Pounding Out Impurities First, the heated steel is struck with a heavy hammer, flattened, and folded—a process called Orikaeshi-Tanren. Comparing the “Lower Forge” (Shitagitae) and “Upper Forge” (Kamikitae) samples on display, you can see the iron becoming denser with every strike, sparks flying as impurities are removed to create exquisite layers. Amata repeated this folding process many times to create the unique “grain” (Hada) of the blade.

- ② Tsukurikomi and Hizukuri (Shaping) By wrapping a soft iron core (Shingane) in hard steel (Kawagane), the sword gains its famous characteristic: “unbreakable and unbending.” It is then hammered out into the familiar sword shape. At this stage, the blade still has no “curve” (Sori).

- ③ Yaki-ire (Hardening): The Moment of Destiny This is the most dramatic stage, where the soul is breathed into the blade. Clay is applied to the surface (Tsuchi-oki), the blade is heated to a high temperature, and then plunged into water. The sudden temperature difference increases the steel’s hardness and simultaneously creates the characteristic curve and the Hamon (blade pattern). This task, where a split-second judgment decides everything, required Amata to reach a state of extreme mental focus.

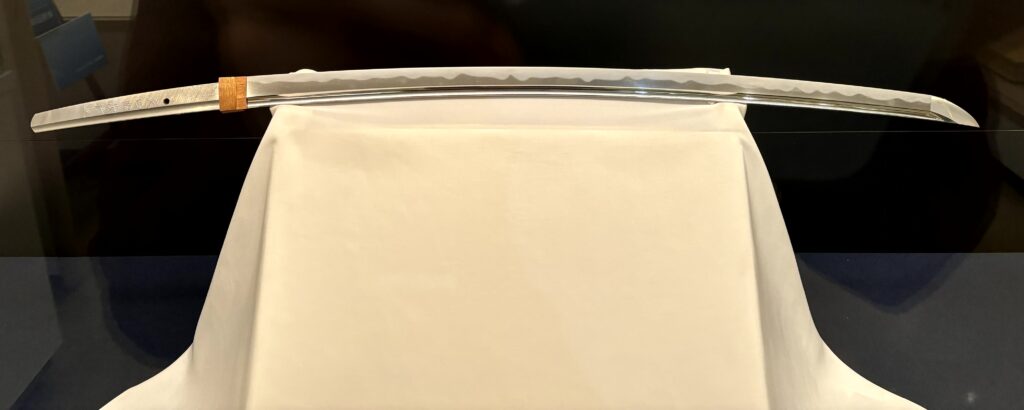

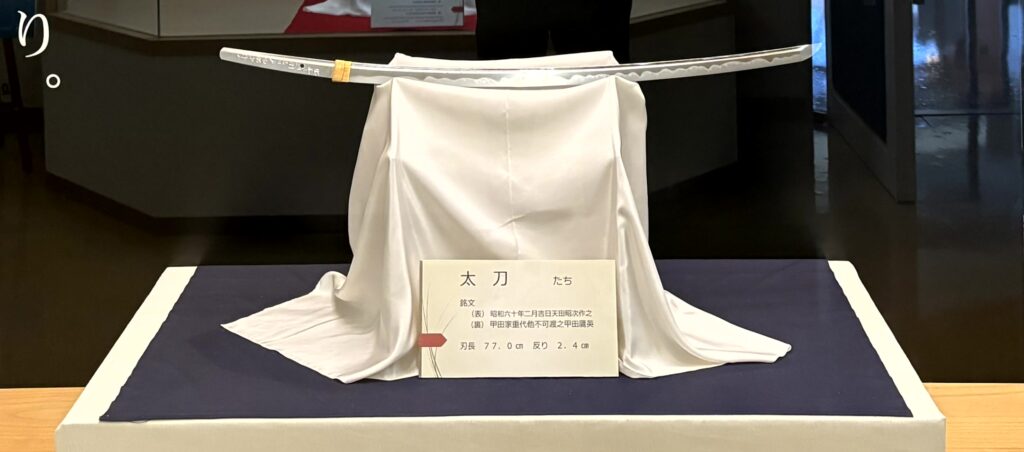

4. Breathtaking Beauty: The Finished Masterpieces

After learning about the process, viewing the finished swords is a completely different experience.

The works of Master Amata sitting in the display cases possess a truly fluid form—a graceful curve pointing toward the heavens and a brilliant white Hamon shimmering along the edge. His Hamon patterns are not flashy; instead, they possess a deep, quiet expression. Changing your viewing angle makes the patterns shift like a moving sea of clouds or crashing waves.

Look closely at the Jigane (surface steel). Thanks to his obsession with smelting his own iron, it has a fine, moist texture often described as having “moisture”—a radiance only found in iron that has truly come to life. These swords have transcended their role as “weapons” to become “works of art,” etched with the history of Amata’s struggle with iron.

5. Inheriting Tradition: The Message of the Museum

A visit to this museum reveals more than just the genius of one man; it showcases the 1,000-year-old tradition of Japanese craftsmanship (Monozukuri) that has continued since the Heian period.

During his life, Amata trained many disciples, passing on his skills without hesitation. He likely felt that the “heart of the Japanese people” found within the sword must not end with his generation.

The museum is popular with families and tourists alike. In a quiet corner, I saw children staring intently at the production samples. “How does this lump of iron become so beautiful?” That simple curiosity is the first step toward connecting culture to the future.

6. Closing the Journey: The Landscape of Echigo and the Sword

Leaving the museum, the lush rural landscape of Echigo (Niigata) stretches out before you. The water he used to forge, the charcoal for the fire, and the scenery he loved—perhaps it was this harsh Niigata winter and the local environment that allowed such resilient and beautiful swords to be born.

If you have the chance to visit Japan, please come here. There are great ski resorts nearby, so you can enjoy some skiing too—Japan isn’t just about Niseko! (haha).

Akitsugu Amata, a man who dedicated his life to a single blade and reached the peak as a Living National Treasure, still claimed he had “much to learn from iron.” By appreciating his swords and learning about his way of life, something will surely resonate within your soul.