In 2015, a research team from the University of Tokyo presented experimental results on the performance of real Katana.

In terms of cutting force, the Japanese sword produced astounding results. The real Japanese Katana cut bamboo with a force of more than 200 N per square millimeter. This is more than three times the cutting force of a high-performance kitchen knife made with modern technology.

The results for durability were even more frightening: after 100 tough cutting tests, the sharpness of the kitchen knife dropped to less than 50%, while the Japanese sword retained 95% of its initial sharpness.

Furthermore, electron microscopy revealed that Real Katana cut surfaces were smooth with an average roughness of less than 0.1 μm. This is 5-10 times smoother than the surface cut by a kitchen knife (average roughness 0.5-1μm). The object cut by a Japanese sword is beautifully split in half.

What is surprising is the fact that such weapons were created so long ago, and that it is virtually impossible with modern technology to reproduce something similar. There are numerous mysteries surrounding the Japanese sword, which is why we handle this product.

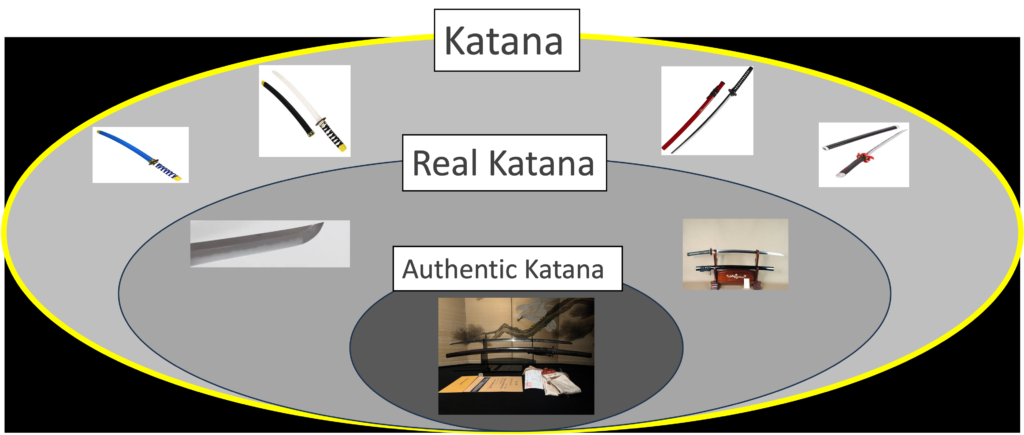

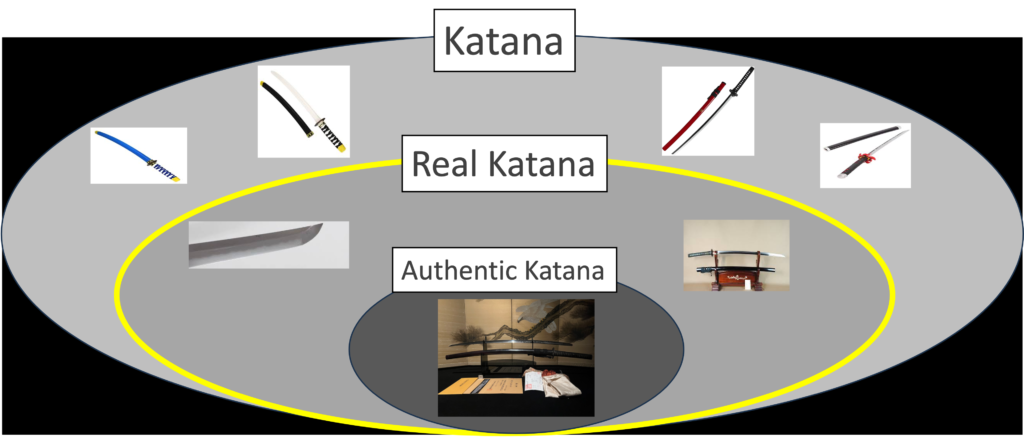

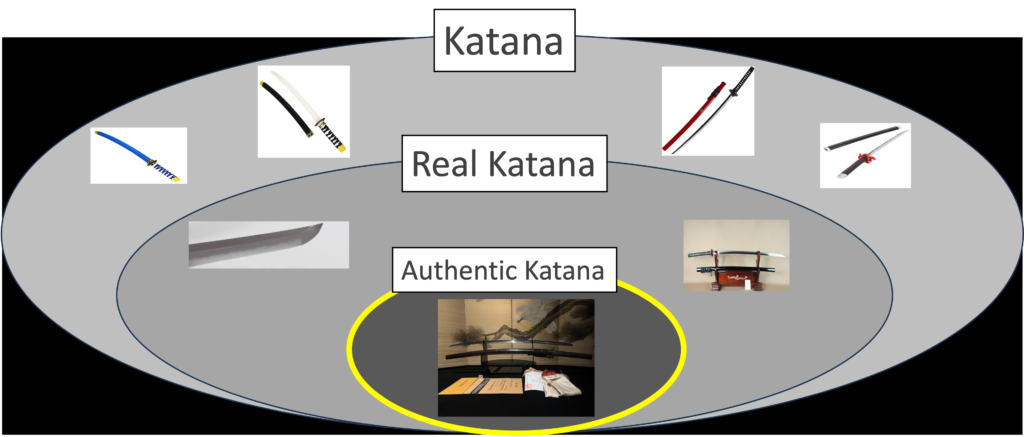

Although there are many Katana-related products available today, there are actually not many Real Katanas with this kind of appeal.

Here we will explain the basic elements that make up a Katana, what makes a Katana Real, and what exactly is the “Authentic Katana” that we deal in.

1. What is Katana(刀)?

What Defines Katana

While the definition of the Katana varies from person to person, the feature that most distinguishes it from other weapons is its shape.

Unlike swords used in many other countries, which are straight with blades on both sides, the Japanese Katana has a curved shape with a blade on only one side.

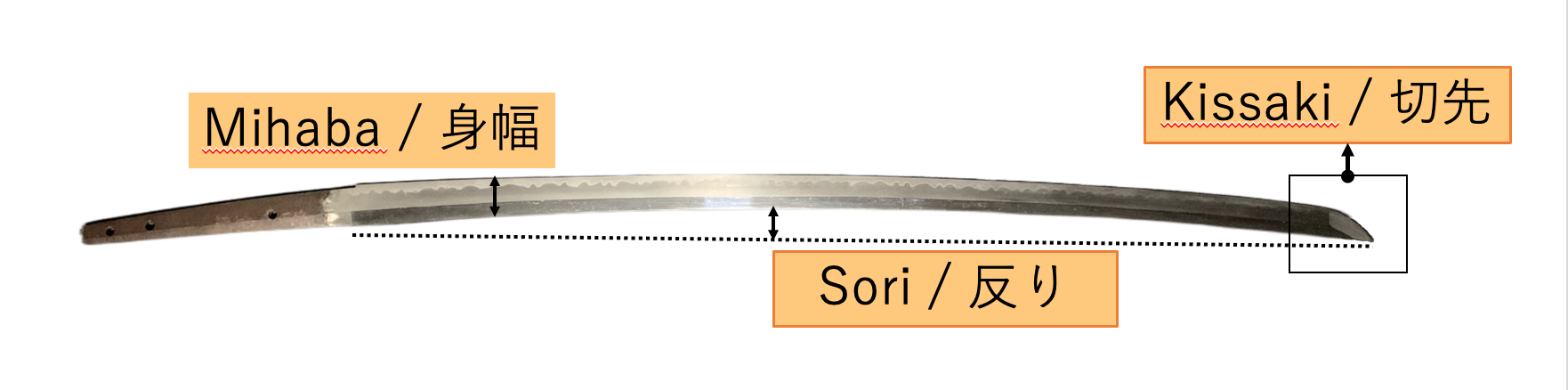

The length shown in the figure above is called the “Sori”. This is a measure of the curvature of the Katana and is the key to its iconic beauty.

Katana is able to cut objects effectively with less force because of this sori. Straight lines are more effective for thrusting movements, and this shows that Katana is made specifically for slashing objects in half.

Katana as a “Weapon”

The history of sword making in Japan dates back to B.C., when straight swords were initially brought from mainland China.

It is believed that curved swords with Sori appeared after the Jouhei-Tengyo wars of 935 during the mid-Heian period (794-1185). This is due to the fact that “Samurai” began to rise around this time.

They were a group that made their living fighting with katana, and they served their masters, the Imperial Court and the Shogunate, with their military prowess.

For the samurai, who basically fought on horseback, the curved sword had a structure that made the most sense. With this curvature, the sword could be drawn quickly in an arc on horseback and used for slashing in the same motion.

This also worked well in quick defense against enemy attacks. Samurais would quickly pull out their Katana on horseback, and then begin fighting without a moment’s pause.

This structure indicates that battles between samurai were settled in an instant, and that the Katana was a weapon specialized for “one-hit kill”. It is a very different aim from the Western sword (a straight sword with blades on both sides), which is designed for thrusting attacks and second swing slashes.

The era moved on to the Kamakura(1185-1333), Nanbokucho(1333-1392), Muromachi(1336-1573), Azuchi-Momoyama(1573-1603), and Edo periods(1603-1868). During all these periods, the Katana has always served as a weapon of the Samurai.

In any age, what is required of a katana as a weapon is its sharpness.

In the Edo period (1603-1867), Yamada Asaemon Yoshimutsu, whose job was to cut heads for execution, tested Japanese swords on the bodies of criminals and rated them as Wazaamono(業物) if they had excellent sharpness.

In order to be called Wazamono, a sword had to be able to make 3 or 4 sharp cuts out of 10 attempts. Katana that were able to cut “greatly” seven or eight times out of 10 attempts were named Saijo-Owazamono(最上大業物).

Katana has been continually transformed by the legendary swordsmiths of each era. It has branched out into various schools and evolved into a wide variety of styles.

Katana as a “Symbol”

During the long period mentioned above (935-1868), the Katana has existed as a weapon of the Samurai, but also as a symbol in many different ways.

First, the Katana is a symbol of the sacred in Japan.

Since ancient times, due to its strong trustworthiness as a weapon and its mystical beauty, it has been believed that the Katana is possessed by a deity and is dedicated to the Gods and Buddha.

These are called Honoto(奉納刀, votive swords), and because they are created for the purpose of pleasing the gods, giant Katana over 3 meters in length were sometimes created.

Also, there is a history of 1,000 beautiful Honotos being dedicated to a single shrine at the behest of the Emperor.

Second, the Katana was a symbol of spirituality.

In Japan, there is a famous saying, “Katana is the spirit of the samurai”. This is an idiom meaning that the Japanese sword is so important to a samurai that his spirit resides in it.

A good Katana can cut an object in half with one straight swing. Samurai believed that humans, like katana, must be straight with their beliefs. This is the foundation of the spirit of “Bushido(武士道)”.

As well as being a symbol of spirituality, the Katana was also a symbol of the samurai’s authority.

Samurai who found their identity in Katana became more concerned with it than with anything else.

The higher-ranking Samurais wore Katana made by famous swordsmiths, along with gorgeous Koshirae, and this was all about their status.

Katana as an “Artwork”

After the end of the Edo period, the Japanese sword was no longer used in actual battles due to the evolution of guns, cannons, and other firearms.

Then, after the Meiji Restoration, the “Sword Abolition Ordinance” was issued, prohibiting all but police and military officials from wearing swords. In this case, Japanese swords were not taken away from the townspeople and samurai families, but were kept in each family as heirlooms handed down from generation to generation.

The real Katana crisis came after World War II, when GHQ(The institution that occupied Japan) announced that Japanese swords and other weapons would be confiscated from private homes.

However, the Japanese government claimed that the confiscation of Katana was a robbery of cultural property, and as a result, only Japanese swords with artistic value were exempted from the confiscation.

The old Katana that survived this process are the “Authentic Katana”, described below.

Prices of Real Katana Replicas

There are now a variety of Katana-related products, including custom-made original swords and very inexpensive Real Katana look-alike products.

A metal product in the shape of a Japanese sword that is not a real Katana is collectively called a Mozoto(模造刀) in Japan.

Instead of using Tamahagane steel (to be explained later) as the blade material, Mozotos are mainly made by alloys such as copper, zinc alloys, and aluminum. Some materials are described as “Damascus steel,” which is made by forge welding several different metals to produce an artificial pattern.

Many vendors now sell these Mozoto as Real Katana. Note, however, that these are not the same as Real Katana as defined by Japanese experts. There are a number of other requirements for Katana to be “Real,” which are discussed below.

Anyway, since genuine Katana are limited in quantity and expensive, the demand for Mozoto as an inexpensive product has been increasing in recent years. Products that allow customization in terms of color and design are popular, and foreign manufacturers also sell these products.

Mozoto’s typical price ranges from 15,000yen to 60,000yen ($100 to $400), and they are purchased by light users who want to easily display a Katana-like figurine.

2. What is Real Katana?

What Defines “Real Katana”

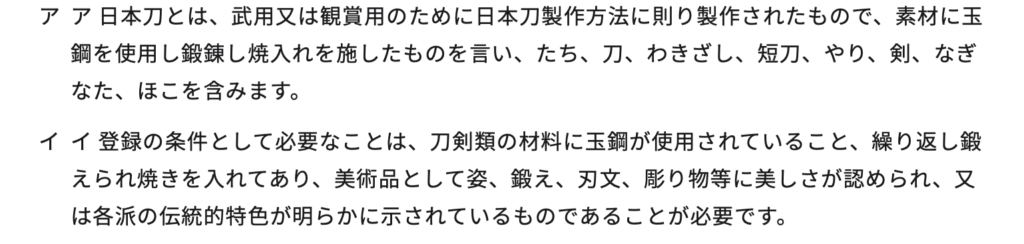

The Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs(文化庁) has a clear definition of Real Katana(Nihonto). It is defined by material and manufacturing method.

“The requirements to qualify as Real Katana(Nihonto) are that it is made of Tamahagane steel, that it is made by traditional methods, and that it is beautiful as a work of art or clearly shows the traditional characteristics of each school.”

In this chapter, we will go further and explain each of the Real Katana conditions set by the Japanese government and how much Real items that meet those conditions are selling for.

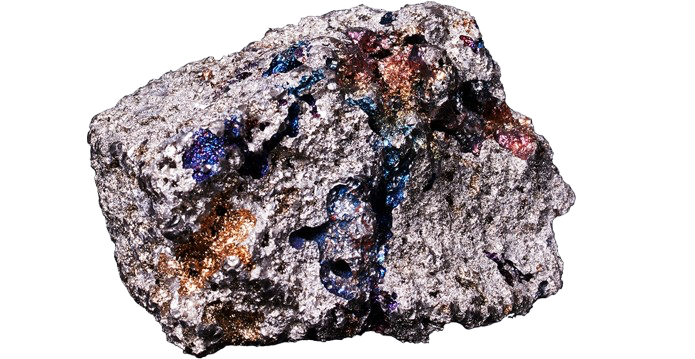

Requirement 1:Made of Tamahagane Steel(玉鋼)

The first condition for Katana to be REAL is that it is made of Tamahagane steel.

“Tama(玉)” in Tamahagane means jewelry, and Hagane(鋼) means steel. The word is derived from the fact that it was treated as something precious from that time.

This steel is extracted in very small quantities through an ancient Japanese process called Tatara Ironmaking(たたら製鉄).

This technique is said to have been studied for more than 1,000 years since the Kofun period(250-538), and was perfected as “Early Modern Tatara” during the Edo period.

The technique was eventually discontinued in the Taisho period (1912-1926), when it was pushed aside in favor of mass-produced techniques amid modern industrialization. Later, the business was revived to make military swords during the war, but by the end of the war, the business was completely discontinued. The company’s reserves of Tamahagane steel ran out.

The Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) and major companies at the time tried to create alternative raw materials using new science and technology, but they were unable to produce raw materials of equivalent quality.

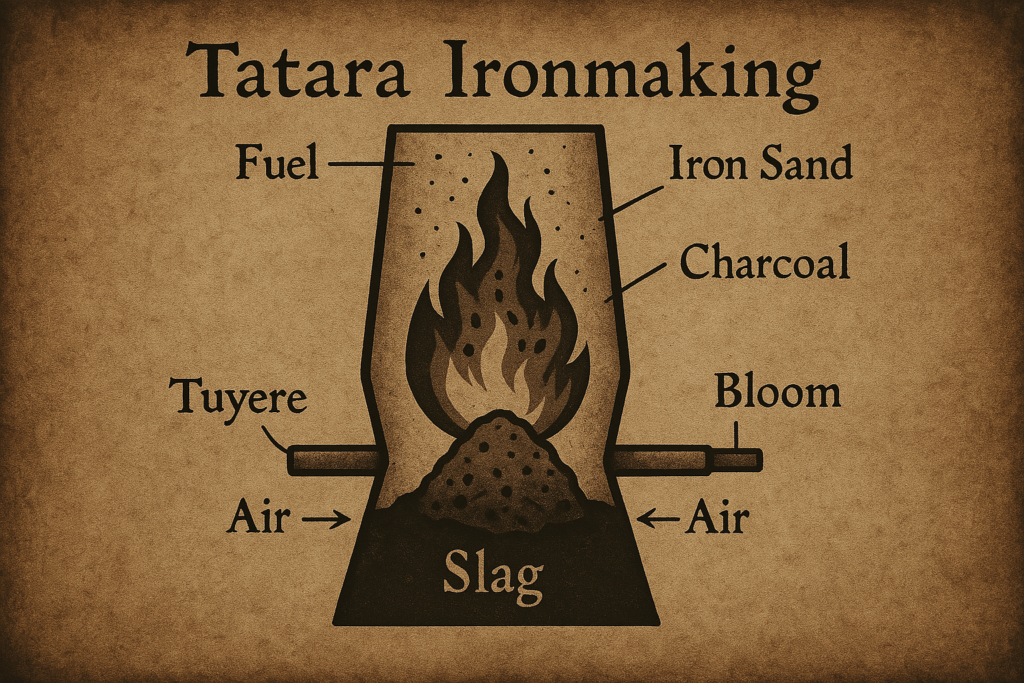

Tatara iron making is a technique that uses iron sand as the raw material and charcoal as the fuel, which combines with carbon to produce steel.

While this method has been used since ancient times in many countries, the distinctive feature of Tatara ironmaking is that it heats iron at low temperatures over a long period of time.

As a result, there is less contamination of iron with harmful impurities such as phosphorus and sulfur, and as a result, iron of extremely high purity can be extracted.

Although not efficient in terms of production, Tatara ironmaking is a method that allows for the refining of high purity steel, and the Tamahagane steel produced by this process is a key element that influences the function and appearance of Real Katana.

In modern times, Tatara iron making is carried on exclusively at “Nittoho Tatara” in Okuizumo Town, Shimane Prefecture.

It is operated by the Nihon BIjutsu Token Hozon Kyokai(NBTHK) with technical support from Hitachi Metals for the purpose of supplying genuine Tamahagane steel.

The Nittoho Tatara is currently the only place in the world where Tamahagane steel can be produced, and this is one of the main reasons why new Real Katana cannot be produced.

Requirement 2:Made by Traditional Methods

Katana has its own manufacturing process, and one of the requirements for Real Katana is that it be made correctly according to this process.

Although the process becomes more complicated when broken down into smaller pieces, here we will divide it into seven easy-to-understand processes and explain their contents.

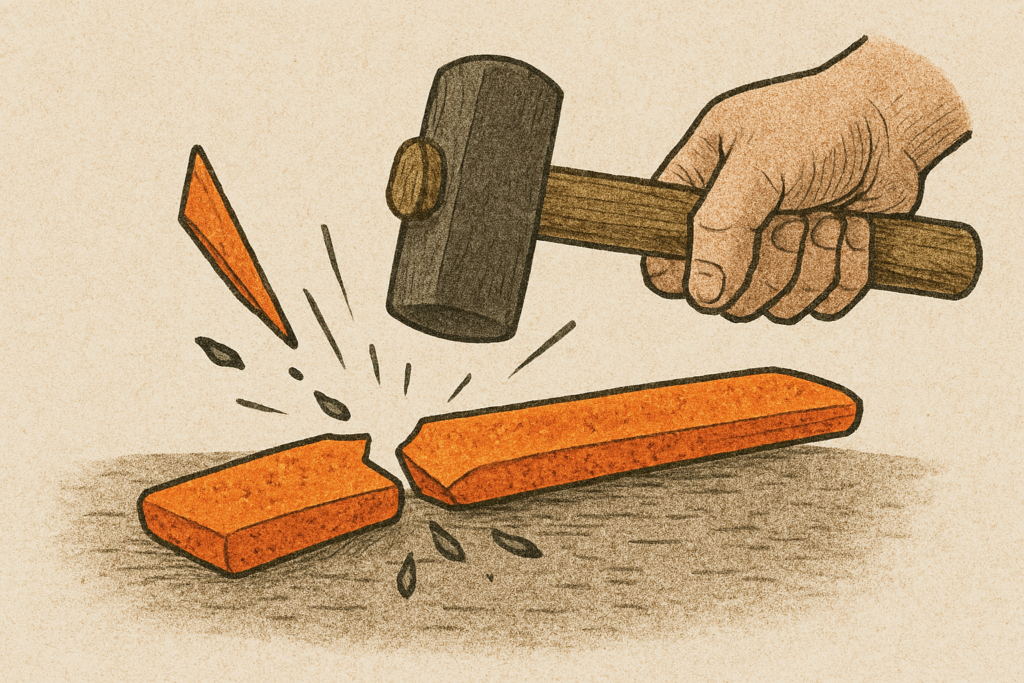

◼︎ Mizuheshi & Kowari(水減しと小割り) : Cool in water and hit with a hammer

The first step is to sort tamahagane steel according to carbon content.

Real Katana uses hard steel with high carbon content for the skin and soft steel with low carbon content for the center of the blade, so sorting is necessary according to hardness (carbon content).

The process involves heating the tamahagane steel until it is bright red, rolling it out into thin sheets several millimeters thick, placing the heated steel in water to cool it rapidly, and then pounding it. Through this process, the hard parts with high carbon content naturally shatter, leaving the soft parts with low carbon content.

◼︎ Wakashi(沸かし) : Heat until melted

Next, the hard Tamahagane steel for the surface area and the softer Tamahagane steel for the inside are stacked separately and they are each heated well to the center. This makes the piled up steel into one lump again.

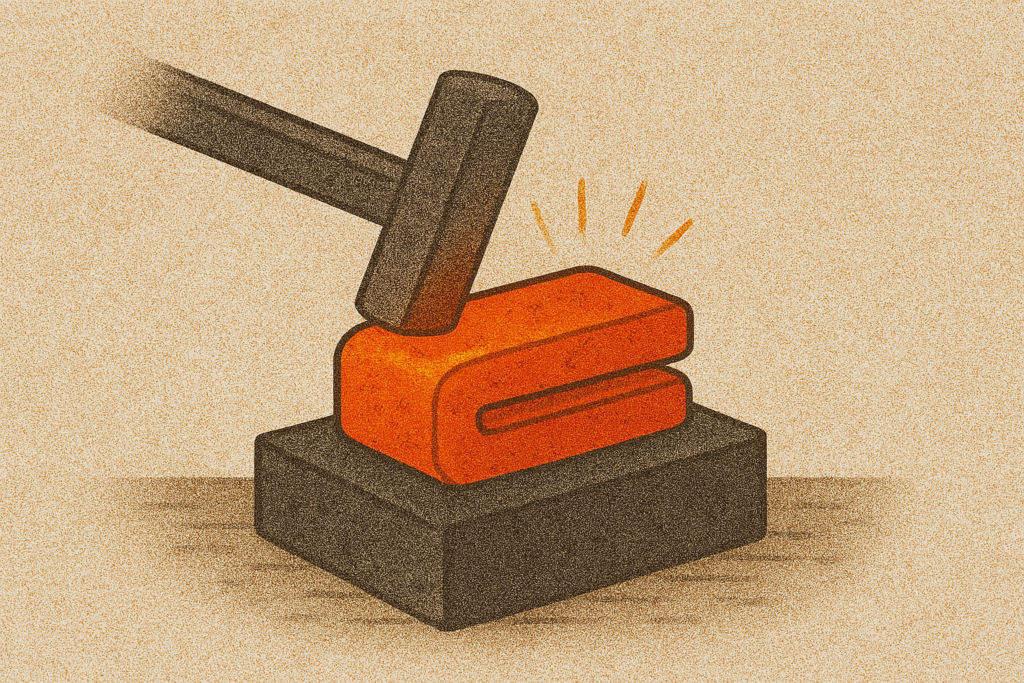

◼︎ Orikaeshi Tanren(折り返し鍛錬) : Fold and refine

Enter the most characteristic process in the creation of Katana. It is called Orikaeshi Tanren, meaning, to forge it by folding it over and over again.

In this process, the well-boiled material is flattened and then folded and overlapped. This is done about 15 times to create 33,000 layers, removing impurities and reducing the carbon content in the process.

Modern science has shown that the Orikaeshi Tanren has a significant effect on the strength of Katana, see this article for more details. → The Secret of “Curvature”

◼︎ Kumiawase(組合せ) : Combine

In this process, the softer steel for the center section is wrapped with the harder steel for the skin section. The greatest invention in Real Katana is this combination of two different hardnesses of steel.

Harder steel is better for a good cut, but softer steel is better for preventing breakage. Real Katana solves this contradiction by using a two-layer construction.

◼︎ Sunobe & Hidsukuri(素延べと火造り) : Stretch and shape

Once the combination of the skin steel and the center steel is complete, it is heated and rolled into a single flat bar. Then, using a mallet or file, it is shaped into a Katana.

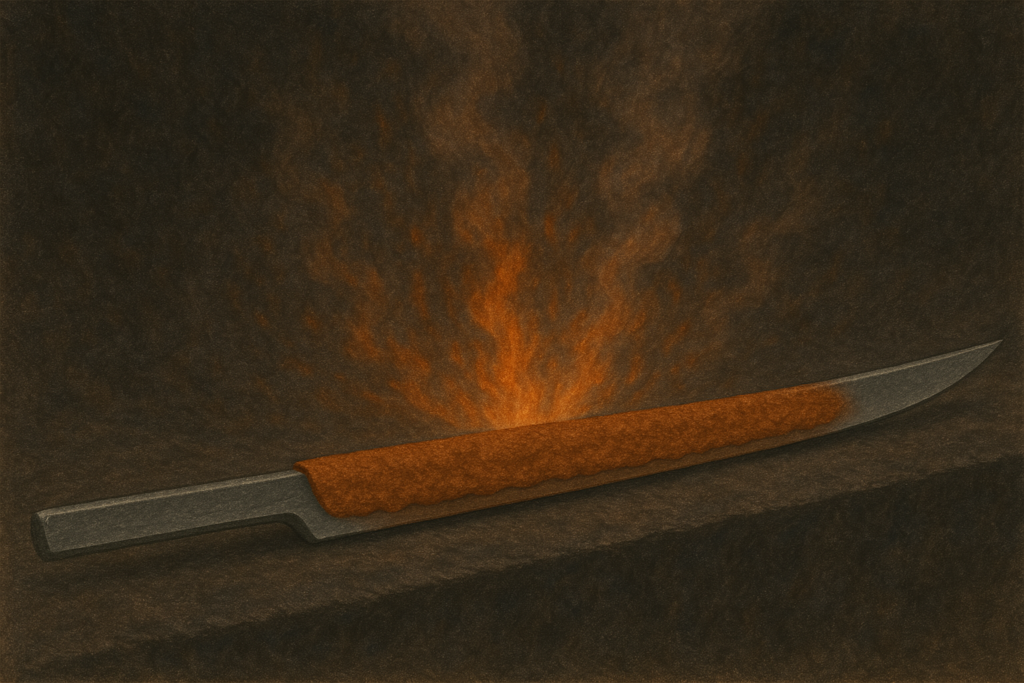

◼︎ Yakiire(焼き入れ) : Apply clay to surface, heat, then cool rapidly

The blade is coated with a clay called Yakibatsuchi in a variety of shades, heated to about 800°C, and then rapidly immersed in water to cool. This process, along with Orikaeshi Tanren, is very characteristic in the making of Katana.

The thicker the coating of clay, the smaller the temperature change, and the thinner the coating, the larger the temperature change.

In the Yakiire process, the temperature change is increased by reducing the amount of clay on the blade side. The difference in the amount of carbon and the difference in the cooling rate causes the expansion rate of the blade to increase, resulting in the warping of the steel. This is the birth of Sori.

What is happening scientifically in this process is also summarized in this article, which you can read if you are interested.

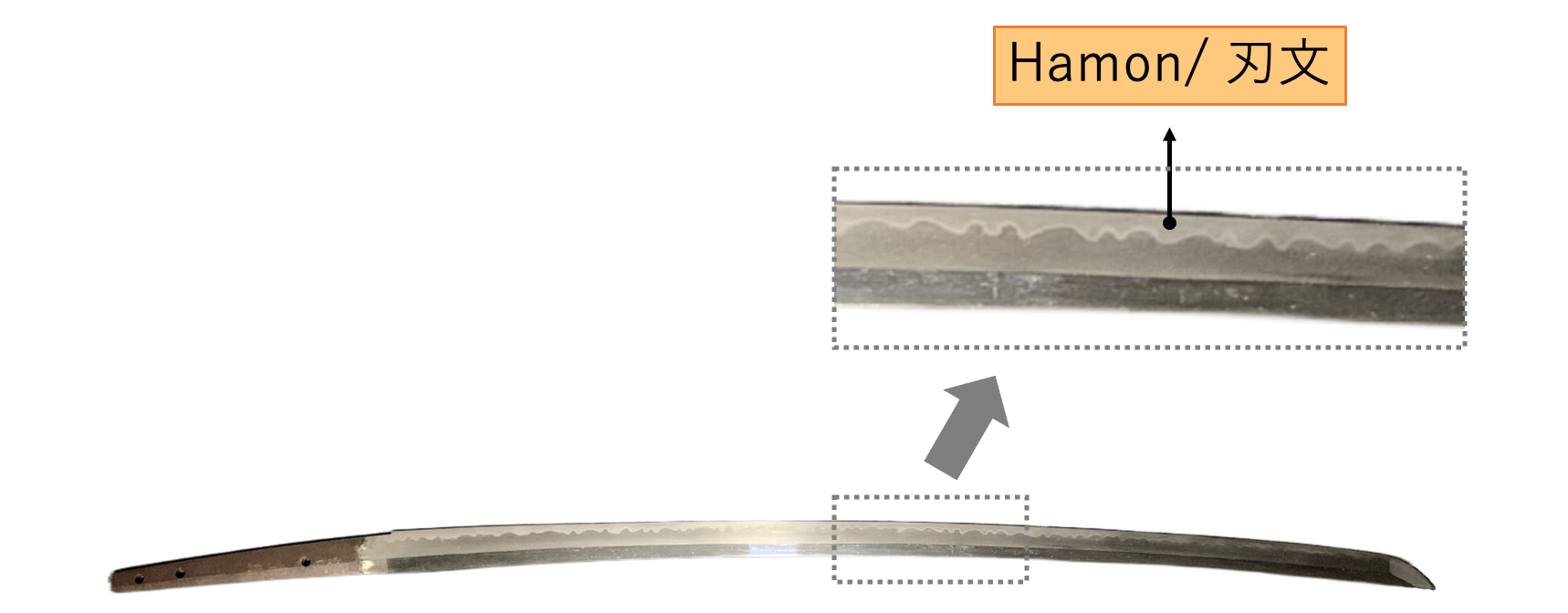

This process of yakiire leaves its burn mark on the area where the clay is placed. This is what “Hamon(刃文)” is all about.

◼︎ Meikiri(銘切り) :

Finally, the entire process is completed by rough sharpening the entire piece, drilling a mekugi hole, and digging the artist’s name (Mei) on the handle.

Requirement 3:Beautiful as a Work of Art

This condition is a bit difficult part to understand. Going back to the formal definition, it is as follows.

“and that it is beautiful as a work of art or clearly shows the traditional characteristics of each school.”

First, let me explain what is meant by “beautiful as a work of art” as referred to here.

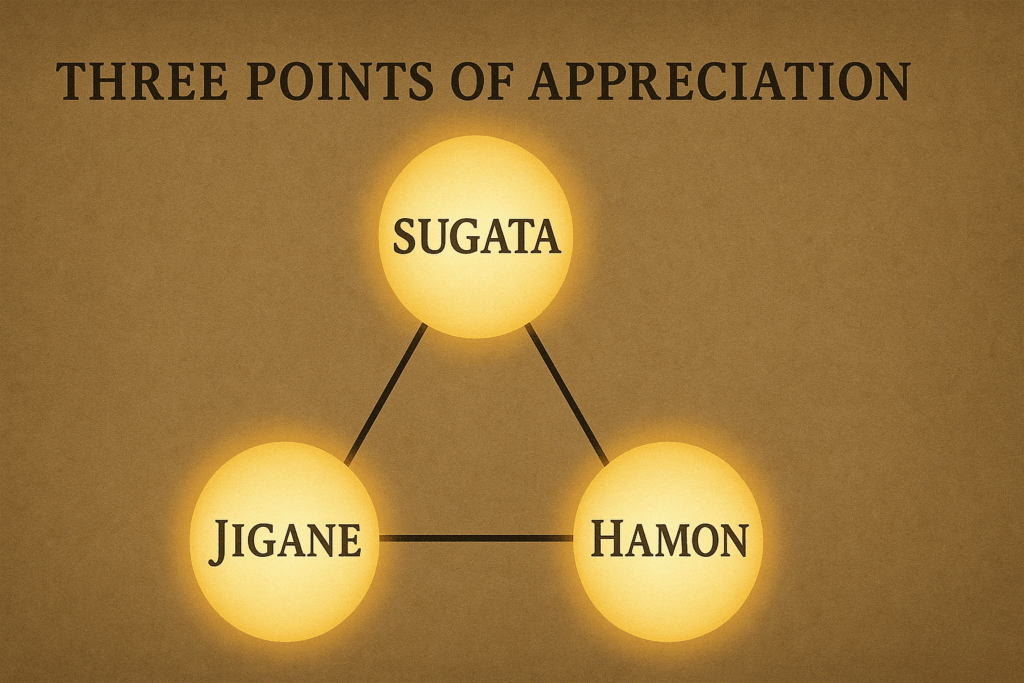

There are three points of appreciation, and in order for a piece to be Real Katana, it must have sufficient appeal in each of these areas.

◼︎ Sugata(姿):Appearance

Sugata refers to the overall shape of the katana.

In particular, check to see how much sori (warp) there is, how much mihaba (width of the blade) there is, and whether the kissaki (tip of the blade) is well made.

If you feel the imposing power that is typical of Katana at the first glance, it is a good Sugata.

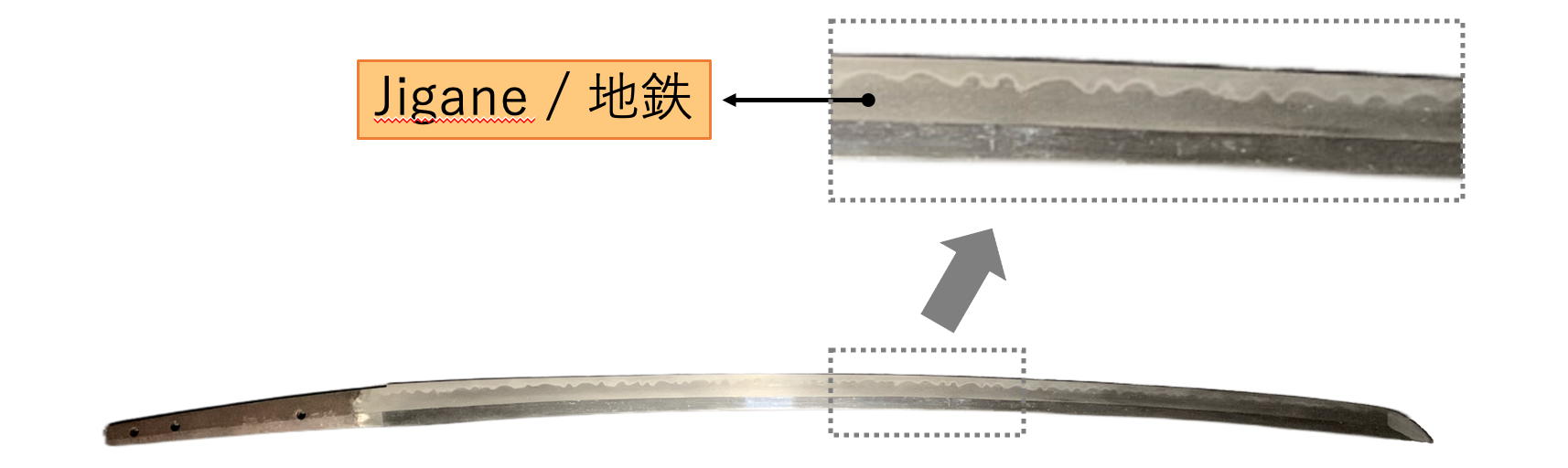

◼︎ Jigane(地鉄):Fine Patterns Appearing on the Surface

Jigane refers to the fine patterns that appear on the surface of a sword blade. It can be observed by staring at a part of the blade while reflecting the light.

If the pattern looks like the grain of a plank of wood, it is called Itame-Hada(板目肌); if it looks like the annual rings of wood, it is called Mokume-Hada(杢目肌); if it looks like a vertical slice of wood, it is called Masame-Hada(柾目肌).

This pattern is the result of the process described earlier of refining by folding over and over again. It is an important point of appreciation because it is all different for each individual Katana.

◼︎ Hamon(刃文):Wave-like Pattern Appearing on the Surface

When you saw a Japanese sword for the first time, you must have been amazed by its gleam. Hamon is a white wave-like pattern that appears on the surface of Katana when it reflects light.

Hamon are named according to their shape, with straight Hamon being called Suguha(直刃) and wavy hamon being called Midareba(乱れ刃).

Among Midareba, a regularly rounded Hamon is called Gunome(互の目), a Hamon that looks like a row of clove fruits is called Choji(丁子), and a Hamon that looks like a large, lazily rippling wave is called Notare(湾れ).

Hamon appears in the Yakiire process described earlier. It is one of the most distinctive designs in Katana and is the area where the individuality of the swordsmith is most strongly expressed.

Requirement 4:Shows the Traditional Characteristics of Each School

Next, we will discuss the traditional characteristics of each school. First, let’s review the definitions.

“and that it is beautiful as a work of art or clearly shows the traditional characteristics of each school.”

As this description suggests, this condition exists as an alternative element of beauty as a work of art.

Please note that this does not mean that “even if it is not beautiful, as long as it shows the characteristics of each school, it meets the requirements”. Rather, it means that “even if it is difficult to identify which school the sword belongs to, as long as the beauty of the sword as a work of art is recognized, it meets the requirements”.

Now, let us explain the schools. In Japan, there are five major katana producing areas where many famous swords were made.

Depending on where the Katana comes from, differences in Jigane and Hamon are evident, and the technique has been considered a secret. As a result, sword making in each of the five regions has evolved in its own unique way.

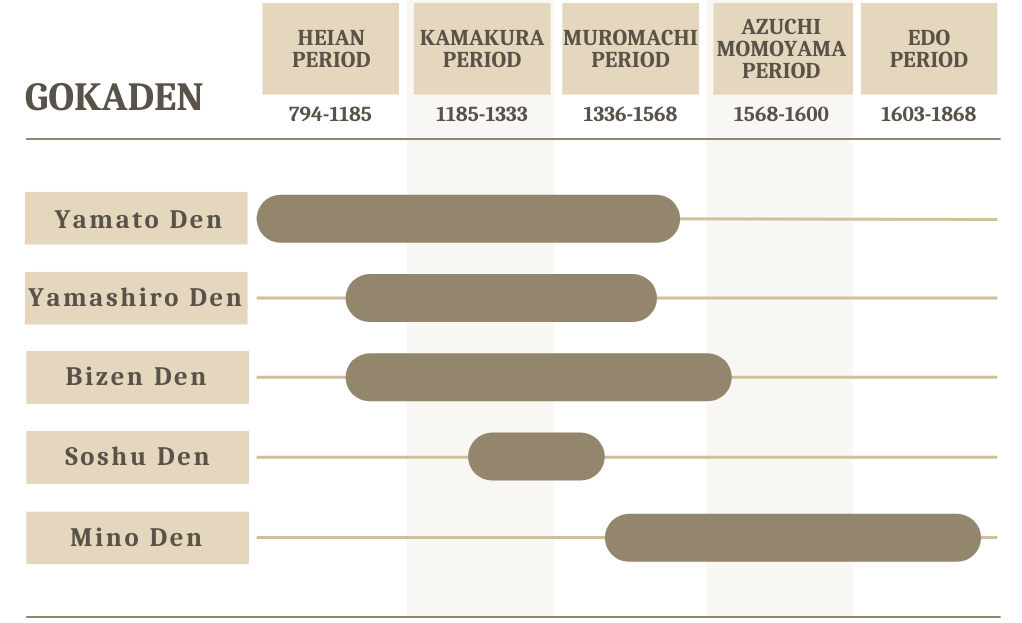

Thus, five representative schools of Katana were born, and these five are collectively called Gokaden(五箇伝). Let us briefly describe the characteristics of each.

◼︎ Yamatoden(大和伝):It was inherited in what is now Nara Prefecture and is the oldest of the Gokaden. It is characterized by a rustic style that, while elegant, is dedicated to actual fighting.

◼︎ Yamashiroden(山城伝):It was inherited in what is now Kyoto, the capital of Japan, which attracted high-quality iron. Its jigane is exquisitely packed, rich and beautiful, and its sugata is graceful and prestigious.

◼︎ Bizenden(備前伝):It was inherited in what is now Okayama Prefecture, one of the largest factions of the Gokaden, characterized by its gorgeous hamon and sturdy blades.

◼︎ Soshuden(相州伝):It was inherited in what is now Kanagawa Prefecture(相模, Sagami). Its Sugata is long and generally warps around the center of the blade, which is its greatest feature.

◼︎ Minoden(美濃伝):It was inherited in what is now Gifu Prefecture. It is the newest of the Gokaden schools and is characterized by a style that is a cross between Yamatoden and Soshuden.

These Ggokaden can be summarized by period as follows.

Many of the older pre-Edo period Katanas have their roots in these Gokaden. These are also the conditions for “Authentic Katana”, which will be explained next to Real Katana. More details will be explained later.

In any case, the last of Real Katana’s requirements in this chapter, “the traditional characteristics of each school,” is a strong reflection of the characteristics of this Gokaden and its derivatives.

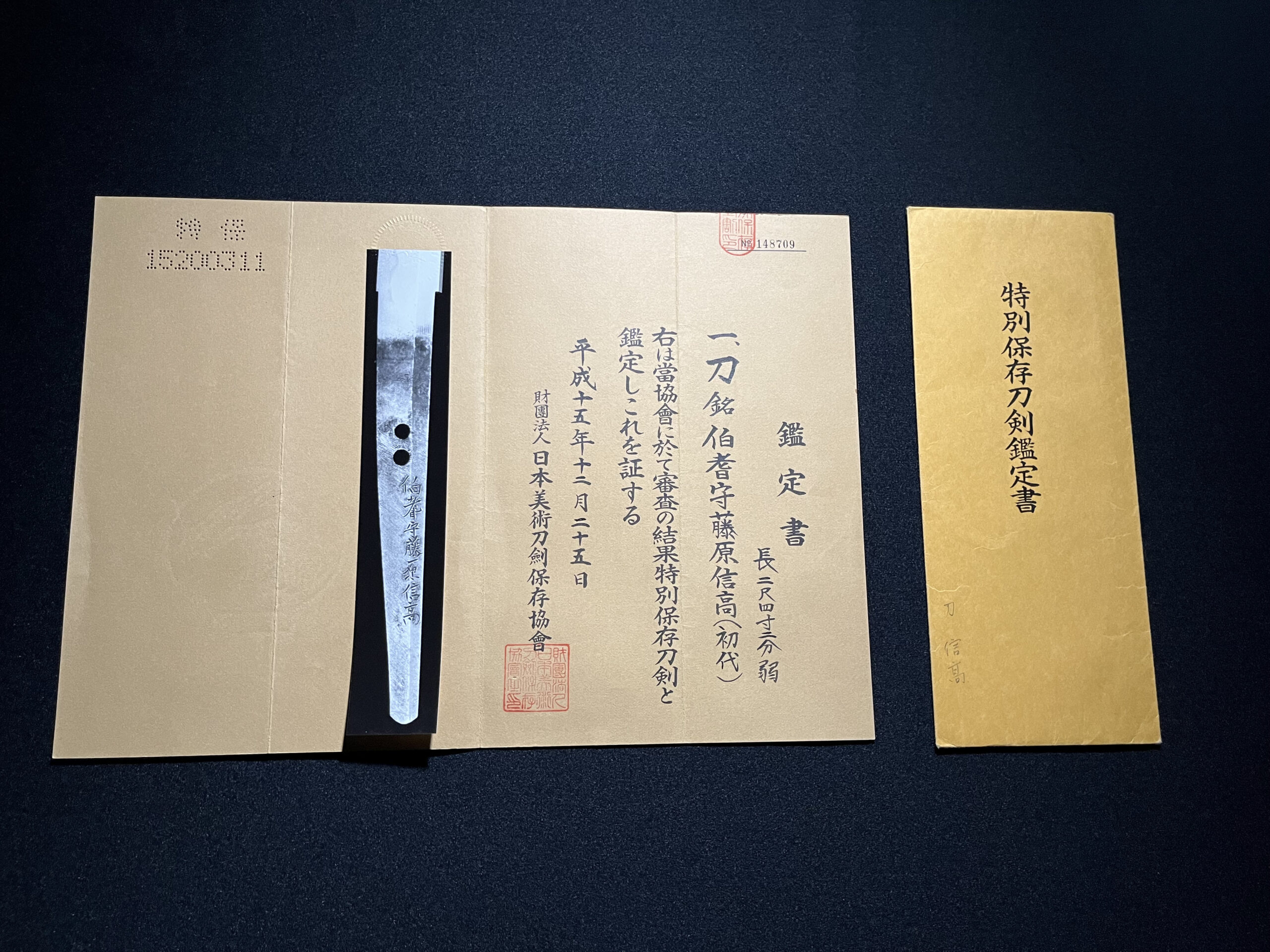

FYI: Is the NBTHK certificate paper proof of Real?

If you are looking for a Katana, you will probably come across one with a certificate.

The most famous one is issued by the Nihon Bijutsu Token Hozon Kyokai(NBTHK), which is currently the most trusted certificate in Japan.

The NBTHK system is that you send your Katana to them and pay a fee to have it examined, and they will give you a certificate with the swordsmith’s name fixed and a grade based on the state of preservation (Hozon-Token, Tokubetsuhozon-Token, etc.).

It is not that easy to say that if it is a Katana with a certificate of NBTHK, it is Real.

Of course, if it has a certificate, it is a minimum guarantee. However, if the Katana is of a certain level, you can get a certificate as long as you submit it for examination, so it is not a guarantee of high quality by itself. There are many good katana that do not have a certificate because they have not been submitted for examination, and even if the same katana is submitted for examination several times, it may be returned with the name of a different swordsmith.

In other words, the correct stance is to consider the certificate as “a guide with a certain degree of accuracy by an expert”. The same applies to certificates issued by organizations other than NBTHK.

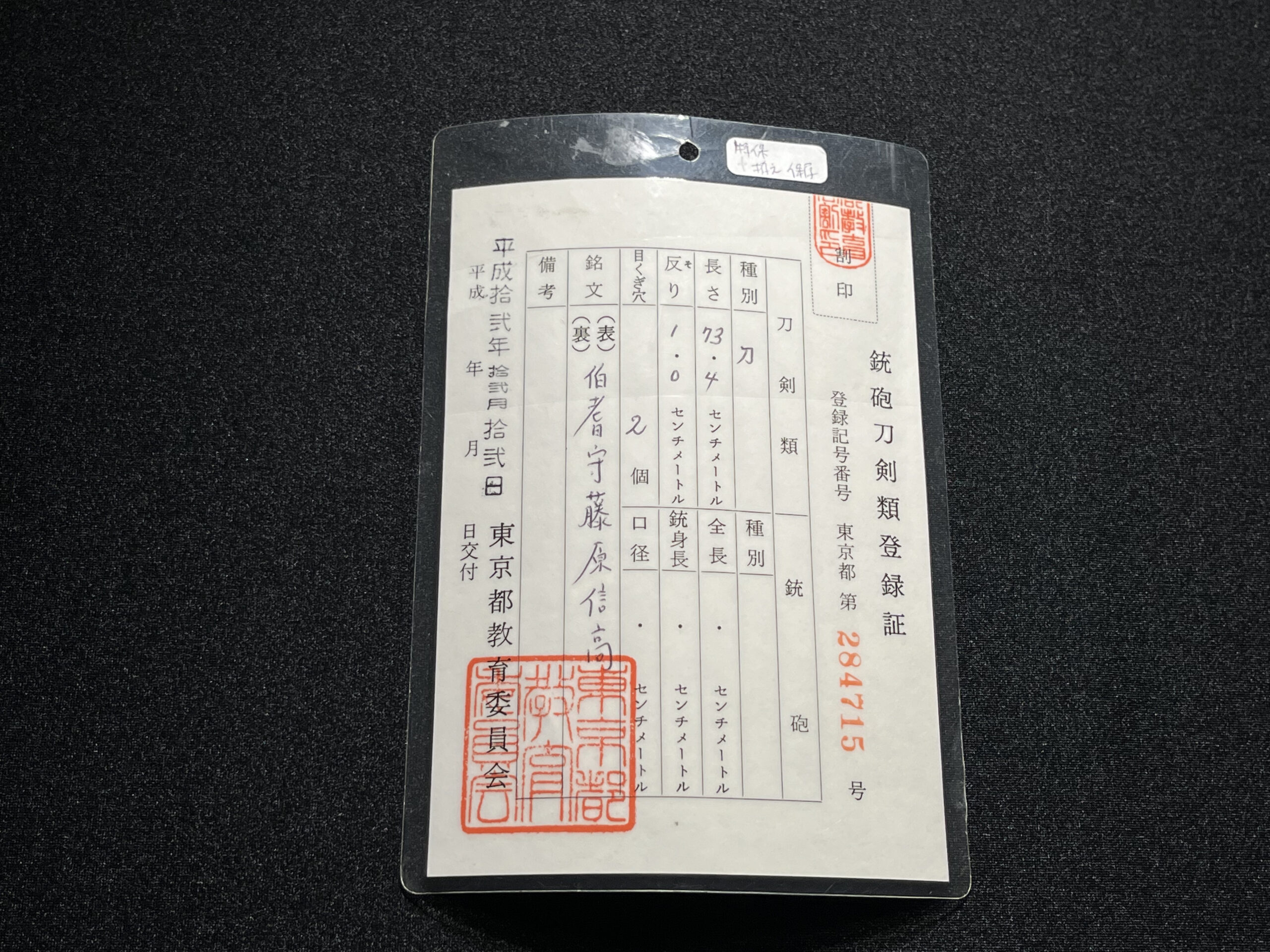

Katanas also often come with a registration certificate(登録証) like the one above.

This is issued by the board of education of each prefecture and indicates that “this sword is treated as a Katana of fine art.

This is not a guarantee of quality at all, but at the very least, it is the national government’s minimum approval to treat the sword as a Katana. The fact that it is attached does not at all mean that it is a good Katana, but on the other hand, if it is not attached, it is out of the question and you should never buy it.

Prices of Real Katanas

Having explained the main conditions for Katana to be called Real based on the country’s definition, let’s look at the price at the end.

A typical Real Katana price is approximately 200,000yen to 2,000,000 yen ($1,300 to $13,000).

Of course, this is in the volume range, and some modern swords made by famous modern swordsmiths can cost close to 10,000,000 yen ($66,000).

Katana that only meet the minimum requirements for Real Katana are generally priced based solely on the quality of workmanship based on Sugata, Jigane, and Hamon. This is a very simple pricing logic, slightly different from the Katana with historical value content, which we will explain shortly.

3. What is Authentic Katana?

What defines “Authentic Katana”

Among Real Katana, those that meet more specific criteria are what we call “Authentic Katana”, and we distinguish them from other Real Katana.

This is precisely the kind of product we specialize in on this site. Furthermore, the idea of introducing such “Authentic Katana” to people overseas was the motivation behind the creation of this site.

In this last chapter, we will briefly explain what makes Real Katana an Authentic Katana.

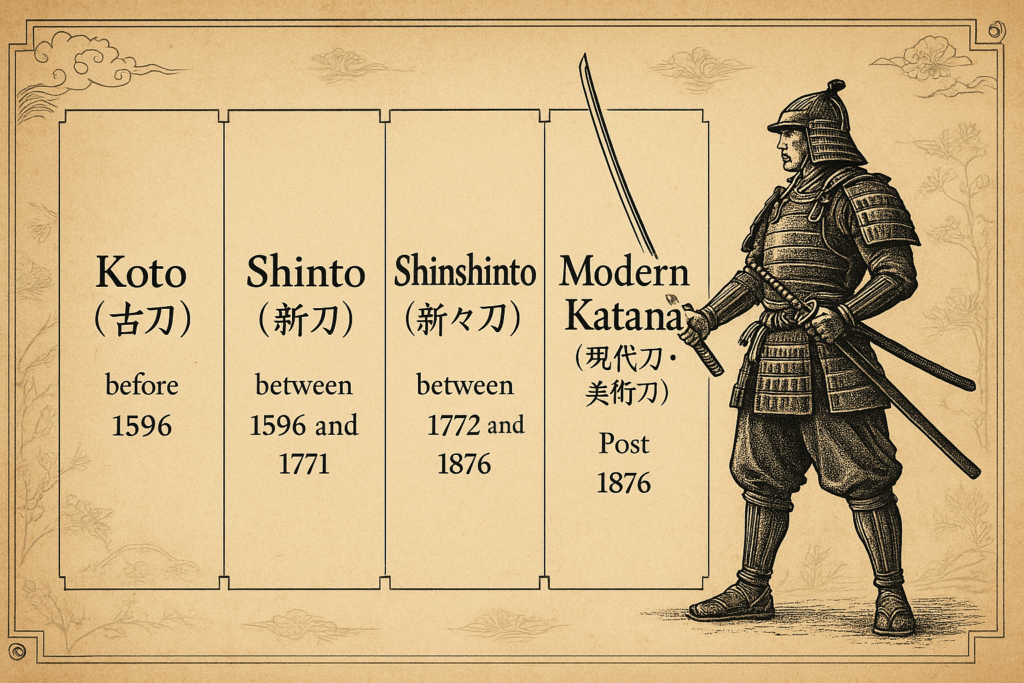

Requirement 1:Historically Valuable (Forged Before 1876)

The first requirement for “Authentic Katana” is that it must contain historical value.

Katanas are generally classified into four types based on the era in which they were forged: Koto, Shinto, Shinshinto, and modern swords.

◼︎ Koto (古刀) — Blades forged before 1596

These swords were forged during Japan’s feudal age, from the Heian to late Muromachi period (approximately 900–1596). Each blade carries the spirit of real battle—wielded by samurai on the battlefield, not merely displayed. Their refined curvature, active hamon, and subtle steel grain reflect both aesthetic mastery and life-or-death purpose. To own a Koto is to hold a living piece of warrior history.

◼︎ Shinto (新刀) — Forged between 1596 and 1771

Crafted in the early Edo period, Shinto swords emerged in an age of peace, yet retained deep roots in the martial tradition. While war had faded, the need for swords as symbols of authority and legacy remained. These blades often feature robust construction, bold hamon, and meticulous detail—preserving the essence of the samurai spirit through a refined artistic lens.

◼︎ Shinshinto (新々刀) — Forged between 1772 and 1876

Shinshinto swords were born at the twilight of the samurai era, forged by swordsmiths seeking to revive the glory of ancient blades. These are not reproductions—they are expressions of resistance against cultural decline, blending classical techniques with Edo-period refinement. They represent the final chapter of true katana forged in the lineage of war.

◼︎ Modern Katana (現代刀・美術刀) — Post 1876

Blades forged after 1868—whether for military use or artistic appreciation—are considered modern. These swords are no longer weapons of war, but rather expressions of craftsmanship. While they may not carry historical significance, many are well-made using traditional techniques. At Ifu, we do not carry modern katana, but we respect the living tradition they continue.

We at Ifu regard Koto, Shinto, and Shinshinto swords as katana with true historical significance.

The historical value of a katana is not determined by its age alone, but by the context in which it was created and used. Blades forged before 1876 carry a unique significance because they were made during a time when the sword was a living part of Japanese society.

Before the Haitōrei (Sword Abolishment Edict) of 1876, the katana was not merely a symbol—it was a functional weapon, a badge of status, and an essential part of a samurai’s daily life. These swords were created for actual use, whether in battle, self-defense, or formal duels, and they reflected the spirit, values, and demands of their time.

After 1876, however, the role of the katana changed dramatically. The Haitōrei outlawed the public carrying of swords, effectively ending the katana’s place as a practical tool in society. From that point onward, swords were no longer forged for use in real-life situations, but instead became objects of ceremony, art, or historical preservation.

While many modern swords are beautifully made and crafted with great skill, they do not exist within the same historical context as earlier blades. They are excellent works of craftsmanship—but they are no longer “living artifacts.” This is why we at Ifu focus exclusively on katanas forged before 1876. These are not just swords. They are pieces of real history.

Requirement 2:Exceptional Craftsmanship

Another condition for a Real Katana to be recognized as an Authentic Katana is that it must exhibit exceptional craftsmanship—even in the eyes of professionals. In other words, it must meet a range of detailed criteria used in katana appraisal, and truly stand out as a superior blade. Swords like this are extremely rare—perhaps one in several dozen Real Katanas meets this standard.

Now, some people might ask: “Isn’t the craftsmanship of a katana just a matter of personal taste?”

And to be honest, you’d be absolutely right. At the end of the day, how a katana resonates with you is entirely subjective. If a blade excites you or feels right in your hands, then for you, that is a well-made katana—and there’s nothing wrong with that.

That said, katanas are objects with a surprising number of points to evaluate. The more katanas you’ve seen, the more you’re able to notice the subtle differences in quality. There’s simply no substitute for experience.

Of course, you don’t have to rely on expert opinion when making a purchase. But people like us—who’ve seen thousands, even tens of thousands of blades—do tend to notice specific details. These fine points lead to small pluses or minuses in our internal evaluation, and ultimately, they influence the price. This is exactly why similar-looking katanas can vary so much in cost.

Earlier, we explained the key points of Sugata, Jigane, and Hamon as the “Three Points of Appreciation” for Real Katanas.

In addition to those, there are many other factors that experts examine when evaluating a Katana. Here, we’ll introduce three such examples that highlight what professionals often look for in more advanced assessments.

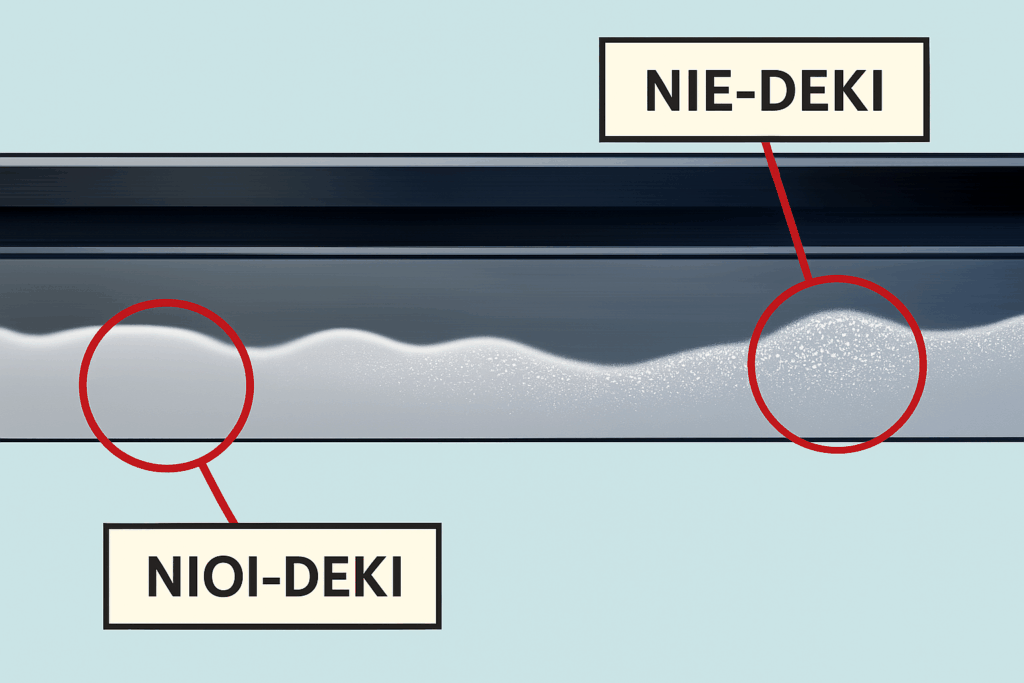

◼︎ NIE vs NIOI(沸か匂):Crystalline Structure in the Hamon

When observing the hamon closely, you can see that it contains distinct regions of differing crystal sizes. These differences are the result of variations in heat treatment temperature during the hardening process.

The granular, glittering particles are called nie-deki, while the softer, mist-like areas—where the crystals are too fine to distinguish—are called nioi-deki.

Nie appears in zones exposed to higher temperatures, while nioi forms in lower-temperature regions along the blade.

If you’re familiar with traditional sword appraisal, you might have seen professionals holding the blade at about a 21° angle to a light source. This specific angle helps reveal the structure of the nie and nioi zones with greater clarity.

There is no universal “better” or “worse” between nie and nioi.

However, this area of the blade often reflects the individual habits and characteristics of the swordsmith’s technique. By carefully studying this detail, we are able to identify with precision which era and school the blade originates from, and make a detailed assessment of its overall level of craftsmanship.

◼︎ The Nakago(茎): What Lies Beneath

Usually hidden beneath the tsuka (handle), the nakago is the tang of a Japanese sword—the internal grip section that connects the blade to the hilt.

It often bears the mei, an inscription that may include the name of the swordsmith and the date of manufacture.

But its importance goes far beyond just the signature.

The nakago holds vital information about the blade’s originality, craftsmanship, and aging process.

By examining its shape, we can determine whether the blade is in its original form or has been shortened (suriage). Just like nie and nioi in the hamon, the nakago also reveals the unique characteristics of the swordsmith’s work. Its geometry, finish, and chisel marks can indicate the specific era and school in which the blade was made.

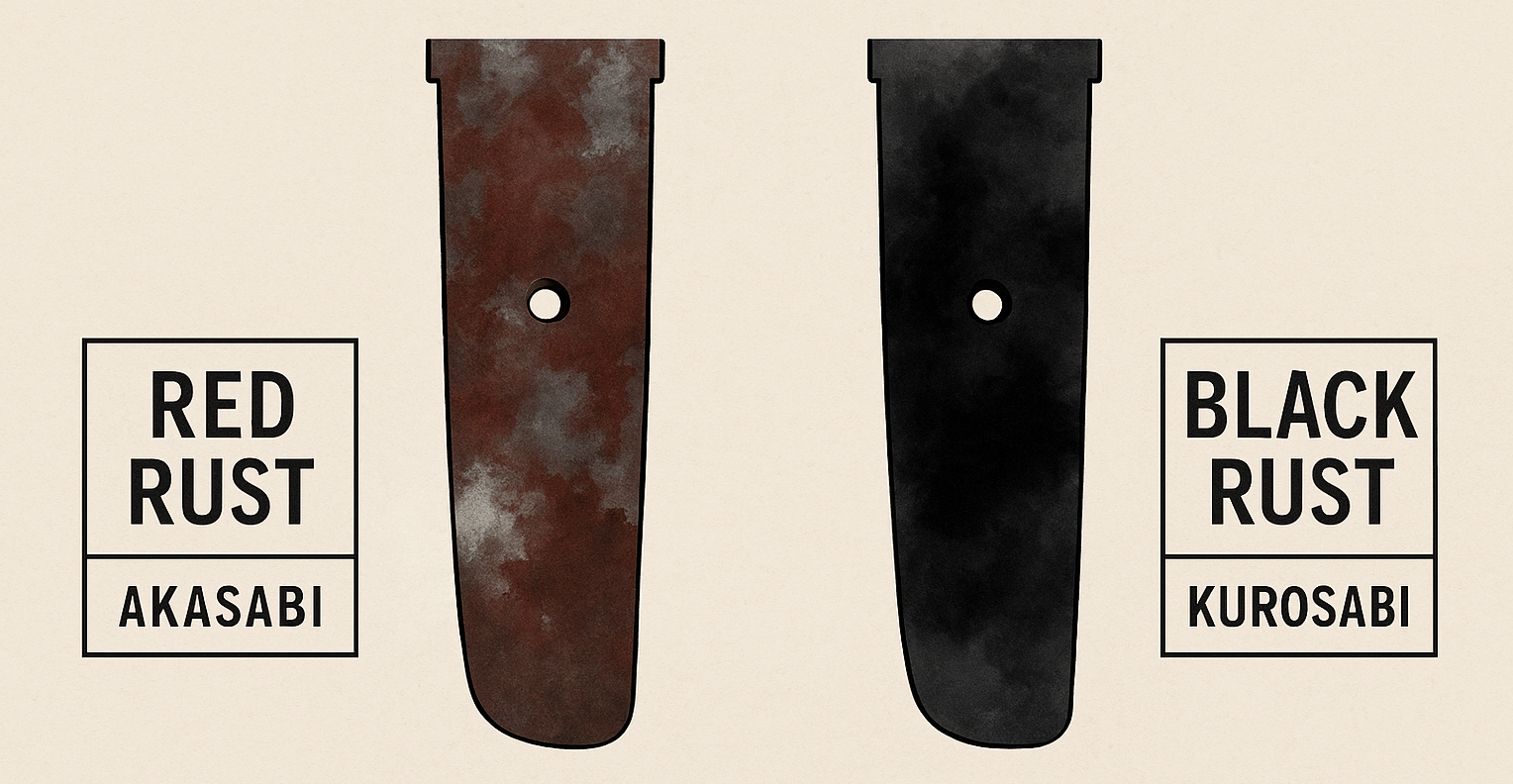

One of the most important aspects when evaluating a nakago is the condition of its rust. Iron—the base material of the katana—oxidizes naturally when exposed to moisture and air, producing rust (sabi).

Red rust (aka-sabi) is a result of uncontrolled oxidation. It has a reddish color, penetrates deeply into the metal, and causes active corrosion. It is considered harmful and undesirable.

Black rust (kuro-sabi), on the other hand, forms a stable oxide layer that protects the metal underneath.

It does not occur easily in nature and often results from long-term aging under ideal storage conditions.

Among black rust finishes, the most highly regarded is a deep, purplish-black tone known as yōkan-iro—named after the traditional Japanese sweet red bean jelly. This coloration is considered a hallmark of proper age, long-term preservation, and historical value.

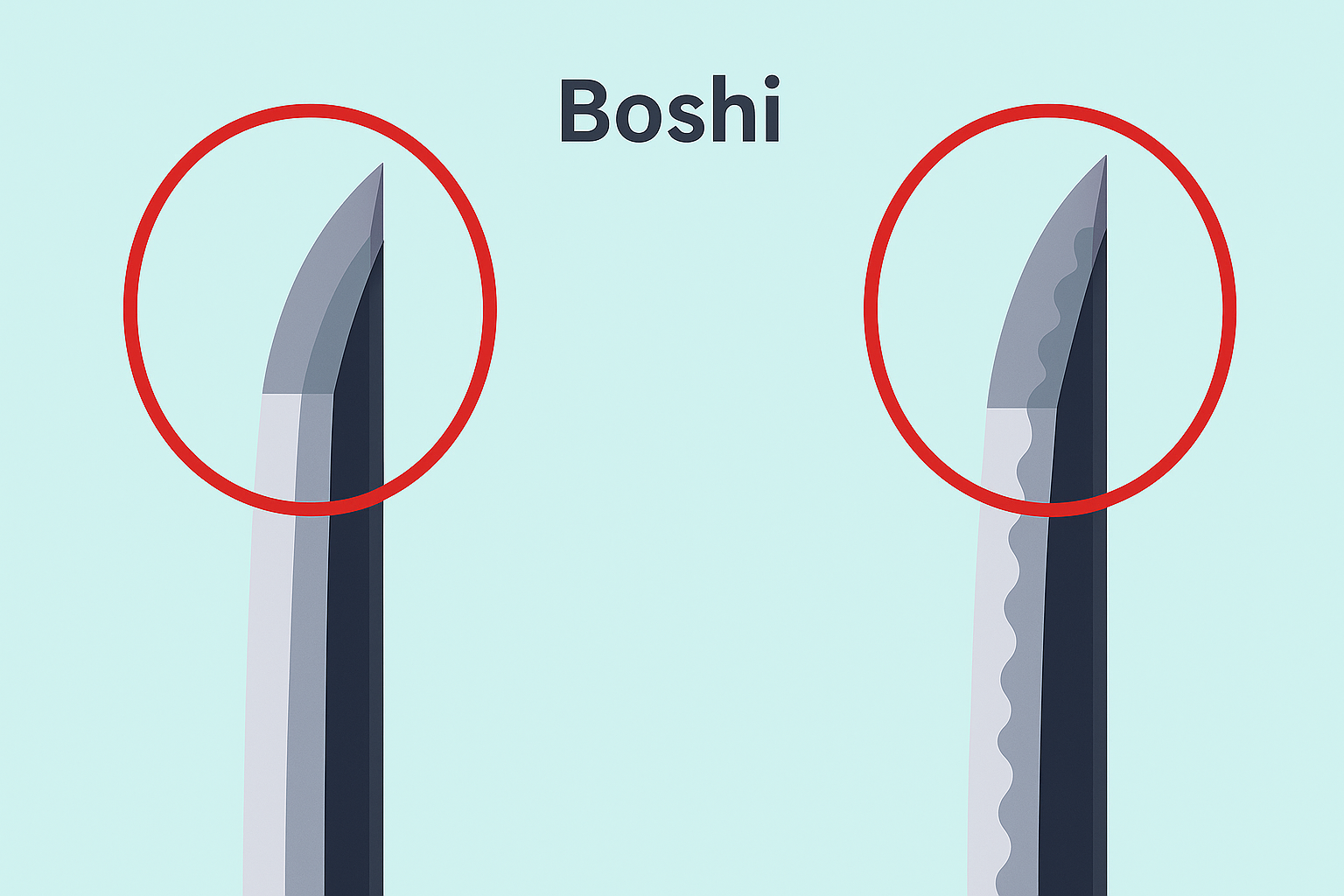

◼︎ The Boshi(帽子): A Reflection of Mastery

In Japanese swords, the hamon that appears at the tip (kissaki) is called the boshi.

There are roughly ten named styles of boshi, depending on its curvature and pattern. Regardless of style, what matters most is whether the boshi is evenly and cleanly hardened.

Because the tip is thinner than the rest of the blade, it is the most difficult area to heat-treat properly, making it a key point where the swordsmith’s skill is tested.

During quenching, the blade must be kept around 750–760°C, the temperature at which steel hardens most effectively. If the temperature exceeds 800°C, the steel crystals grow too large, increasing the risk of structural defects such as hagire(micro-cracks). In the worst-case scenario, the blade may even break.

The kissaki is one of the smallest and thinnest parts of the katana, which means it heats up quickly and is especially vulnerable to thermal damage. A beautifully executed boshi is not only visually striking but also a clear indicator of the smith’s mastery of heat control and blade hardening.

Prices of Authentic Katanas

Among Real Katanas, we use the term Authentic Katana to refer to those with significant historical value and exceptional craftsmanship.

Naturally, these pieces are priced higher than standard Real Katanas.

Even the most reasonably priced Authentic Katanas typically start around ¥700,000, and for particularly rare or important examples, prices can reach well above ¥20,000,000.

There is no fixed upper limit.

Some Authentic Katanas are recognized as National Treasures due to their extraordinary historical significance.

These pieces are strictly protected and cannot be exported from Japan under national cultural property laws.

Because the value of an Authentic Katana is determined by complex and subjective factors—such as historical background and the quality of the craftsmanship—pricing can vary greatly depending on the dealer.

As a buyer, it’s important to keep this in mind and proceed with caution.

There’s no universal answer to how one should assess the value of a katana.

For most people, it’s simply not feasible to physically handle and examine hundreds of swords to develop an eye for it.

In reality, your best option is to find someone—or some place—you trust, and make your purchase based on that trust.

That said, we believe it’s worth remembering one thing:

Even the words of so-called experts should ultimately be taken with a grain of salt.

The true value of a katana isn’t determined by others—it’s decided by you.

If a katana stirs something in your heart, then for you, that katana is unquestionably Real.

Closing Thoughts

This has been a long read, but we hope it helped clarify what a katana truly is, what we mean by a Real Katana, and what qualifies as an Authentic Katana within that category.

Whether you’re thinking of purchasing a Japanese sword or simply want to deepen your understanding, we hope this guide serves as a helpful reference.

As professionals—and enthusiasts—we continue to study the katana from both academic and collector perspectives.

Alongside this, we regularly offer a small, carefully curated selection of Authentic Katanas for sale each month as our “Curated Katanas of the Month.”

While the number of pieces is limited, we take great pride in their quality.

Feel free to take a look.

— From the team at 威風(Ifu)